一世。

后理性主义异端学者文卡特什·拉奥 (Venkatesh Rao) 的热尔韦原理 ( The Gervais Principle ) 自称是一本商业书籍。

实际上,它要求了很多东西。据其介绍:

据我估计,这本书的素材已经触发了。 . .在过去的四年里,成千上万人的危险反思。它为我认识的几十个人引发了重大的(但并不总是积极的)职业变动。

和:

获得组织知识是有代价的。这种能力,一旦获得,就不能不获得。就像学习一门外语会让你对曾经体验过的那种语言的原始、难以理解的声音充耳不闻一样,学习阅读组织意味着你永远无法像以前那样看待它们。达到组织素养甚至流利并不意味着你会做伟大的事情或避免做愚蠢的事情。但这确实意味着你会发现对自己在做什么以及为什么对自己撒谎要困难得多。它迫使您拥有自己做出的决定并接受自己行为的后果……因此,寻求组织素养也意味着对自己的生活负有许多本能地拒绝的责任。

这种力量可能会产生非常不可预测的影响。如果您选择获得它,您可能会发现自己希望自己没有。因此,获得组织素养是一些人喜欢称之为模因危害的东西:可能会伤害你的危险知识。一个案例“无知是幸福的,聪明是愚蠢的”。 […]

但我相信,与《几个好男人》中的杰克·尼科尔森不同,几乎每个人都有“处理真相”的能力。当然,你们中的一些人可能最终会因为这本书而变得沮丧,或者做出错误的决定,但我相信这是与任何内容的所有写作相关的风险。

一本关于管理的书的大谈。

Rao 本人并没有声称这一点,但有几个人说我应该读这本书来理解雅克·拉康(我被特别告知要“尽可能按字面意思理解”)。因此,我怀疑Gervais的“商业书籍”声明至少是不完整的。

二、

1969 年,劳伦斯·彼得提出彼得原则:“每个人都被提升到无能的水平”。也就是说,如果你的工作很出色,你就会不断得到提升,直到你达到你不擅长的水平,然后留在那里。这对于一本商业书籍来说也具有奇怪的哲学意义。

1995 年,斯科特亚当斯反驳了更加愤世嫉俗的呆伯特原则:“公司倾向于系统地将不称职的员工提拔到管理层,以使他们脱离工作流程”。

2009 年,Rao 撰写了《热尔韦原理》 ,延续了越来越犬儒主义的趋势。以办公室作家 Ricky Gervais 命名的原则是:

反社会者,为了他们自己的最大利益,故意将表现出色的 [无能的人] 提拔为中层管理人员,将 [表现不佳的人] 培养成反社会者,并让普通的最低限度努力的失败者自生自灭。

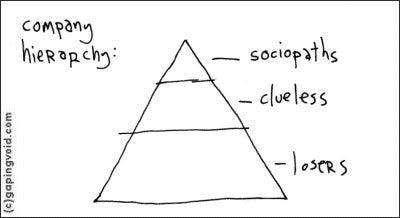

Rao 很快介绍了“Clueless”、“Loser”和“Sociopaths”作为艺术术语。他承认将它们从 Hugh MacLeod 的漫画中提取出来,并因此承认它们的内涵与他所指的真实类别不太匹配。

反社会者不一定是邪恶的(尽管他们经常如此,而 Rao 本人——一个自认反社会者——确实写了另一本书,名为《稍微邪恶:反社会者的剧本》)。他们是雄心勃勃的人,他们宁愿成功也不愿被人喜欢。甘地(根据 Rao)是一个反社会者,因为他能够将自己与传统道德分开并有效地追求目标。 The Office的例子包括 David Wallace 和 Charles Miner。

无知的人不一定是傻子。他们可能是脑外科医生或火箭科学家。但他们根本无法把握社会现实不断变化、难以辨认的本质。他们退回到客观现实——在他们的对象级工作中表现出色——并且非常认真地对待官方的清晰规则。他们可以仔细研究使命宣言,试图找出如何最好地体现其价值观。或者在走廊张贴鼓舞人心的海报。或者试图赢得最佳办公室士气的曲棍球比赛,这样他们就可以获得一等奖披萨派对或其他什么。办公室的例子是 Michael Scott 和 Dwight Schrute。

失败者不一定是坏的、不快乐的或地位低的。他们是广大的常人,不具备以上两种条件。他们喜欢友谊,喜欢积极的情绪,喜欢团体,喜欢社会地位——不是“成为神皇”的意思,而是“被人喜欢”的意思。他们有点了解社会现实,但本能地选择了平静的生活而不是权力意志。办公室的例子包括 Stanley Hudson 和 Phyllis Vance。

在 Rao 对 Gervais 原则的陈述中:

-

反社会者经营公司。

-

他们认为表现出色的入门级员工是无知的(你为什么会表现出色?除非你有明确的途径将你的成功转化为额外的金钱或权力,否则你只是无缘无故地给公司免费劳动力)。他们将他们提升为中层管理人员,在那里他们可以充当有用的马屁精和棋子,永远无法预测不可避免的背刺。

-

他们将表现不佳的入门级员工视为潜在的新反社会者。反社会者意识到入门级的工作是“一笔不划算的交易”,并立即开始谋划升职。这些方案通常非常聪明,但并不涉及在其对象级位置上做得很好。领导力使这些人走上高层管理的轨道。

-

他们将表现完全符合预期水平的人识别为失败者,他们了解他们的讨价还价(以预期水平表现以换取薪水)并接受它。领导力使这些人永远处于入门级左右,而失败者对此很好。

如果这没有意义,请与(如 Rao 一样)普鲁士将军 Kurt von Hammerstein-Equort 的名言进行比较:

我将我的军官分为四个等级;聪明的、懒惰的、勤奋的和愚蠢的。 . .世界上90%左右的军队都是愚蠢和懒惰的人,他们可以用于日常工作。聪明勤劳的军官适合。 . .人员任命。 [但是]聪明和懒惰的人是为了最高的命令;他有处理所有情况的气质和神经。

三、

这就是本书开始展现其本色的地方。在陈述了热尔韦原理之后,它从一本商业书籍转变为一部精神分析著作。

(在我跟进之前,一个警告:就在一个句子中,埋在书的中间,Rao承认每个人都有一点Loser,Clueless和Sociopath,每个人在不同的时间出现. 然后他再也没有回到这个主题,并将它们视为完全不同的类型。我将跟随他的领导并做出此致谢,但也主要将它们分开处理。)

在你脑袋的某个地方有一个麦克风。它在你的内心产生了一个小声音,你非常渴望得到他的认可。你会做任何事情让声音喜欢你。鬼魂、心智模型和拟人化的抽象概念相互争斗,争夺麦克风的转身权和隐含控制你行为的权利。谁赢?

如果您回答诸如“我父母的模糊抽象影子”或“我所有教师的总和”或“规则”或“权威”之类的问题,那么您就是无能的。

如果你回答类似“Mrs. Grundy”或“我必须跟上的琼斯”或“思想正确的社会”,在 Rao 的世界里,你是一个失败者。

如果你回答“我徒手扼杀了所有这些概念,然后用锤子砸碎了麦克风”,那么你就是反社会者。

Gervais 原则对开发心理很重要:

这是重要的东西,被压缩成三个方便的法则:

你的发展是由你的长处而不是你的弱点来阻止的。

发展受阻行为是由基于力量的成瘾引起的

平庸的人比有才华或没有才华的人发展得更快

看待这三个定律的另一种方法是注意防御机制防御机制出现以维持成瘾,即使最初滋养它的发展环境消失了。不过,防御机制作为现象学的部分目录比作为基本思想更有用。

这些就是热尔韦原则的发展心理学根源。回想一下,无知伴随着过度表现。这种过度表现是由于围绕一种力量的发展停滞不前,而这种力量被一种令人上瘾的社会奖励环境所吸引。平庸是你对成瘾的最好防御,也是进一步开放式心理发展的保证。

是的,对于那些发现联系的警觉者来说,停滞的发展是积极心理学意义上的优势的阴暗面。在一种情况下的优势只是在另一种情况下根深蒂固的停滞发展。

在我们的模型中,三个发展阶段——无知者、失败者和反社会者——对应于不同的发展停滞模式和不同的力量成瘾。

也就是说,发展涉及从一个阶段(例如学校)发展到另一个阶段(例如现实世界)。但是,如果你在早期阶段表现得太好了,你就会习惯于从成功中获得的回报。假设你喜欢学校并且做得很好。然后你被邀请参与现实世界,一个明显不像学校的环境。你尝试一下,而不是一直得到赞美/奖励/验证,你很少或根本没有得到这些东西。如果可以的话,也许你回到学校(即获得博士学位),这是一个有其自身问题的策略。但是,如果你不能在现实世界中真正回到学校,相反,你可能会永远停留在一个心理阶段,一切都感觉像学校,你试图扭曲你的看法,直到你的世界模型看起来有点像学校,并且您可以在其中使用您的学校技能和应对机制来应对一切。

我刚刚给出的关于学校的具体例子是 Rao 对 Dwight Schrute 的解释:

德怀特有着严格的德国教养,缺乏对儿童早期创造性表现本能的正常鼓励(我们看到了一些这样的一瞥,包括他在带孩子上班时试图向孩子们阅读可怕的中世纪警示故事天,以及他自己对童年的描述,这使得他的兄弟实际上发育障碍)。因此,他并没有发展出让迈克尔陷入困境的童年寻求掌声的表演行为上瘾。

相反,德怀特在以成绩为导向的学校世界和各种中世纪公会式的世界(如农业、畜牧业和空手道)中找到了解脱。他试图理解管理的世界,这绝对不是一个等级或行会的世界,完全基于外围的行会元素。他是唯一一个对迈克尔安排的幸存者式继任者选择活动感到兴奋的人(在途中的公共汽车上,他问道,“会有商业寓言吗?”)。当他试图操纵时,他的思绪自然会转向隐藏的麦克风、篡改的文件和其他从间谍小说中学到的商业元素,很少会转向心理学。他赢得了偶尔的战术胜利,但无法参加或赢得击败反社会者所需的心理游戏。

在德怀特的世界里,一切值得学习的东西都是可教的,奖章、证书和精英机构的正式成员资格就是成功的证据。即使在游戏行为方面,世界上的德怀特也更容易迷失在积分规则世界中。值得注意的是,德怀特从未看过/读过《查理和巧克力工厂》 (这是关于创意表演的游戏) ,但却痴迷于游戏世界和科幻/奇幻宇宙。

也许德怀特需要正式从属关系的最明显例子是他对内幕单口喜剧节目《贵族》的蹩脚尝试。对德怀特来说,一切都是一场正式的较量,总有权威人物提供合法性和排名。他没有幽默感(由于跳过了童年早期),并且不知道如何真正引起笑声,所以他试图在他能看到的唯一正式会员测试中取得高分,即讲贵族笑话的能力。相比之下,迈克尔至少可以讲青少年笑话,而安迪可以处理一些糟糕的兄弟会男孩幽默。

Rao 认为,节目中的“老板”迈克尔斯科特被困在一个更低的水平:

正常环境中的小孩子通过创造性的表现赢得他们的第一次胜利:背诵童谣、画画和展示创造性的游戏行为。如果他们成功太多,他们就会沉迷于典型的成人反应:哇,你不是很可爱/聪明吗?并且,在较小程度上,受到弟弟妹妹的钦佩。在学习在这种特殊的奖惩环境中茁壮成长时,小孩子主要依赖于对他们所听到和看到的情感内容做出反应,因为他们不太了解。

加入了一些进化的防御机制,以防止不符合童年环境的成人现实,这正是迈克尔的感觉。当他听到有人说话时,他听到的只是“等等等等,干得好,等等,你怎么能做到这个迈克尔?”结合面部表情和肢体语言。

迈克尔的脑袋是一个庞大的库,其中包含各种情况、固定短语和反应之间的幼稚映射。他对自己的行为和言论并不完全负责,因为他真的不理解它们。迈克尔所说的有连贯性。他听起来并不完全是荒谬的,因为他对肢体语言、面部表情和情感暗示做出了有意义的反应。 “你在和我说话吗?” (从德尼罗借来的)是一条好战的台词,当他感到受到威胁时,他会拔出那条台词,然后用笑声来化解紧张,迈克尔能够使谈话脱轨。他标志性的笑话, “她就是这么说的!”是一个极端的例子。在他小跑的大多数情况下,这没有任何意义。其唯一目的是化解紧张局势并取代威胁。与迈克尔一起大笑或沮丧地举起双手对他来说都是胜利。唯一有效的反应是冷静地忽略他的破坏性行为,等待反应平息,然后以主导模式继续对话,就像塞萨尔米兰和他的狗一样……在帕克周围,他的粗鲁朋友,侮辱和客观化谈论女性的方式获得批准,所以他借来的,厌恶女性的男人谈话。在他的政治正确员工的集体注视下,“尊重女性”之类的短语会变得微笑并停止皱眉,这就是他提供的。

[…]

原因如下:妄想是封闭的逻辑方案,现实通过防御机制被扭曲为固定脚本的服务,其余的意义被抛弃了。要制造原创思想,您必须以开放的方式看待/聆听现实的数据。这就是为什么迈克尔的数据库里充满了电影台词。电影是罐装情境反应的金矿,不需要太多现实数据即可检索。当孩子们引用成人或电影时,他们看起来很早熟,并获得了认可。在这个由电视养育的孩子多于父母养育的时代,鹦鹉学舌的电影台词比重复从父母人物或教堂和寺庙中学到的溴化物更自然。

回想一下,无论您是否掌握以前的阶段,社交日历都会迫使您通过后期阶段。那么后期呢?迈克尔不像德怀特那样迷恋奖牌和证书,因为(作为一个糟糕的学生)他从来没有很好地获得它们,因此不会对它们严重上瘾。

最后,Michael 的同侪关系驱动力很差。他想成为关注的焦点,而不是一群同龄人中的一个。当迈克尔似乎在同侪关系驱动下运作时(安迪的那种),他实际上是在将孩子的行为塑造成青少年的模式。他认为特定的人,而不是正式或非正式的群体, 很酷或令人钦佩(代理父母形象,年长的兄弟姐妹)。如果他们不酷或不令人钦佩,则必须让他们认为他很酷且令人钦佩(弟弟妹妹)。

附录中的一行让我印象深刻,说这与纳粹官僚处于同一水平。只是为了好玩,让我们比较一下 Rao 对 Michael 的其他个人资料与 Arendt 对 Adolf Eichmann 的个人资料(所有引述均来自我在耶路撒冷的 Eichmann评论):

尽管控方千方百计,但所有人都看得出,这个人不是“怪物”,但确实很难不怀疑他是小丑。而这种怀疑对整个事业来说都是致命的,而且也很难维持下去,鉴于他和他的同胞给千百万人带来的痛苦,他最坏的家伙几乎没有被注意到。对于这样一个人,他首先非常强调地宣称,他在糟糕的一生中学到的一件事就是永远不应该宣誓(“今天没有人,没有法官可以说服我一个宣誓的声明。我拒绝它;我出于道德原因拒绝它。因为我的经验告诉我,如果一个人忠于他的誓言,总有一天他必须承担后果,所以我一劳永逸地决定不世界上的法官或其他权威将永远能够让我宣誓宣誓,提供宣誓证词。我不会自愿这样做,也没有人可以强迫我“),然后,在被明确告知之后如果他希望为自己的辩护作证,他可以“在宣誓或不宣誓的情况下这样做”,毫不犹豫地宣布他更愿意在宣誓的情况下作证?

和:

当法官最终告诉被告他所说的只是“空谈”时,法官是对的——除了他们认为空虚是假装的,而且被告希望掩盖其他虽然可怕但并非空洞的想法。这个假设似乎被艾希曼惊人的一致性所驳倒,尽管他的记忆力很差,他逐字重复相同的常用短语和自创的陈词滥调(当他确实成功地构建了自己的句子时,他重复了它,直到它变成陈词滥调)每次他提到对他很重要的事件或事件时。无论是在阿根廷还是在耶路撒冷写他的回忆录,无论是对警察审查员还是对法庭,他所说的总是一样的,用同样的词表达。听他说话的时间越长,就越明显地发现他不能说话与不能思考密切相关,即不能站在别人的角度思考。无法与他进行交流,不是因为他撒谎,而是因为他周围有最可靠的保护措施,可以防止言语和他人在场,因此也可以防止现实本身。

最后(这次是我的声音):

如果[阿伦特]有什么论点,那就是艾希曼相信比他自己更伟大的东西。我们通常鼓励这种事情,但我认为亲社会版本涉及到一个特定的比你自己更大的事情。艾希曼(阿伦特说)一般来说只是喜欢比他自己更大的东西,而纳粹对种族霸权永恒斗争的愿景是他能在附近找到的最大的东西。我们稍后会看到他对犹太复国主义者有一种奇怪的尊重,这是因为他们也相信比自己更伟大的东西。艾希曼臭名昭著的陈词滥调是浮华、环境、荣耀和豪言壮语的陈词滥调,这些陈词滥调让他觉得自己在从事一项伟大的事业,无论背后是否有任何东西。他既不承认“只是听从命令”,也不承认个人对反犹太主义的深刻信仰,原因是他对希特勒的忠诚既不来自于此。当希特勒说要杀死所有的犹太人时,他欣然答应了;如果希特勒说要杀死所有的基督徒,他也会这样做。不是因为他是一个听命于拯救自己皮肤的无人机,而是因为他相信。没有纳粹意识形态的任何细节。甚至在希特勒的个人判断中也没有。就在当时发生的任何事情中。

四。

当他进入下一个关于失败者的部分时,Rao 基本上忘记了发展心理。这是一本关于地位经济学的书。

饶诗意的描述:

他们每个人——他们构成了人类的 80%——都是世界上最美丽的婴儿。每个人都是高于平均水平的孩子;事实上,整个 80% 都在人类的前 20% 中(那里挤满了人)。每个人长大后都知道他或她在某些方面非常特别,并且注定要过一种他或她“注定”过的独特生活。

在他们陷入困境的二十多岁时,每个人都在寻找他们所知道的真爱,等待着他们,以及他们在生活中的真正使命。每次他们在生活或爱情上失败时,他们的朋友都会安慰他们:“你是一个聪明、风趣、美丽、才华横溢的人,你对生活的热爱和你真正的使命就在某个地方。我只知道这一点。”朋友们当然是对的:每个人都嫁给了世界上最美丽的男人/女人,发现了他/她的使命,并成为世界上最美丽婴儿的骄傲父母。最终,他们每个人都退休了,获得了一块金表,有人发表演讲,宣布他或她是一个了不起的人。

你和我都知道他们是失败者。

成为失败者意味着坚持认为自己很特别,同时也被你的社会群体完全接受(事实上,你的特殊性只在工具上和其他人欣赏你的情况下才重要)。但是这两个必要条件是 Scylla 和 Charybdis:太坚持要真正的特别,你是一个每个人都讨厌的自恋者;过于胆怯地寻求接受,你承认别人比你好。

Rao 将 Loserdom 视为处理这一悖论的一系列阴谋。最终的解决方案看起来像“每个人都以自己的方式很特别”。

输家动态是 很大程度上是由 Lake-Wobegon 效应的雪地工作推动的,这些工作掩盖了普遍的平庸。但与无知者的错觉(我们上次看到的邓宁-克鲁格品种的错误信心)不同,这种错觉是通过受骗者本身的激烈努力和绝望的否认来维持的,失败者的错觉是由群体维持的。你挠我的妄想,我就挠你的。如果你同意称我为迷人的博主,我会称你为深思熟虑的评论家。而且我们都会说服自己,我们的生命应该被这些不同的衡量标准所重视。

高于平均水平的失败者通常不是基于彻头彻尾的谎言。不像迈克尔自诩为喜剧天才,这完全不正确,帕姆确实是这个团体中最好的艺术家。错觉不在于对她的艺术技巧的错误评价,而在于群体选择首先以艺术为基础来评价她。

换句话说,失败者太聪明了,不会自欺欺人。他们签订了社会契约,要求他们互相欺骗 […]

在生活剧本层面,玩游戏的社会契约创造了名义上的完全模糊性。一个群体中的每个人都是根据一个自定义的生活脚本来判断的,这使得无法比较该群体中的两个生活。帕姆的生活有一个救赎剧本,基于她是办公室里最可爱的人,会画画,并与吉姆形成“它”夫妇。凯文是基于他在一个乐队的事实。 Creed 的独特之处在于他的古怪……记住,你是独一无二的,就像其他人一样。

第二个推论悖论:格劳乔·马克思开玩笑说,他不属于任何愿意接受他为会员的俱乐部。但是,为什么人们会在俱乐部里结交呢?

假设你加入了一个对你来说显然不够好的俱乐部——也许你是一位著名的亿万富翁,他们是一群每周在地下室看一次烂电视的失败者。你为什么会在这个俱乐部?但是假设你想加入一个显然对你来说太好的俱乐部——你是一个没有社交技能的穷人,而你申请到富豪的亿万富翁的乡村俱乐部。为什么他们会接受你?这表明人们不会加入地位比他们高或低的俱乐部。但是他们为什么会加入地位更高或更低的俱乐部呢?难道你不希望没有人加入任何事情,除非他们的地位和俱乐部的地位完全一样,这种情况极为罕见?

Rao 试图表明所有协会都需要某种程度的身份难以辨认。如果你完全了解状态——如果你在额头上纹了“状态:6.8/10”——那么你会看到一个俱乐部,其所有成员的状态都是 6.2 – 6.5,并且知道你可以做得更好。因此,同样的社会阴谋让人们相信他们有有用的才能,也让地位难以辨认。这采取了每个人互相取笑的形式,创造了一个持续不断的轻微状态增加和减少的搅动,这太复杂了,任何人都无法正确跟踪。

(Rao 说,任何群体中的最高和最低地位的人有时都可以清晰地辨认——为群体中的人的地位创造了一个可观察的范围,即“我们适合 6/10 到 7/ 10”——但中间部分必须始终难以辨认,以允许大多数人保留他们的礼貌虚构,即他们是他们群体中地位较高的成员之一。)

本节关于地位经济学的部分以题外话结束。不像敲敲门的笑话。一个人取笑另一个人,以牺牲他们为代价获得地位的笑话。这类笑话是地位经济学交易。

根据 Rao 的说法,最小可行的失败者笑话是三个人:小丑、受害者和观众。小丑开了个玩笑。受害者有机会反驳(例如“需要一个人知道一个!”),而观众决定如何在心理上更新每个人的状态。

Rao 使用了The Office 的例子,但我没看过,所以我在想Seinfeld的一集:

当乔治在一次会议上给自己吃虾时,赖利说:“嘿,乔治,大海在叫。他们的虾快用完了。”机智的乔治直到后来才想到卷土重来,一边开车去网球俱乐部见杰瑞。他的复出是:“哦,是的,Reilly?嗯,混蛋店打来电话,他们快没你了。”

Jerry、Elaine 和 Kramer 并不认为“jerk store”是一次好的回归,主要是因为“没有 jerk store”。伊莱恩建议,“你的头盖骨打了电话。它有一些空间可以租用。”杰瑞建议,“动物园打来电话。你应该六点回来。”克莱默最终认为乔治应该告诉赖利他和妻子睡了。

在发现赖利从洋基队被解雇并现在为凡士通工作后,乔治飞往俄亥俄州的阿克伦市只是为了尝试 jerkstore 线。然而,当他这么说时,赖利回答说:“有什么区别?你是他们有史以来最畅销的书。”对此毫无准备的乔治最终使用了克莱默的产品线。然后他被告知赖利的妻子处于昏迷状态。

Rao 问道:Reilly 在什么意义上成功地“得分”了 George?假设乔治是一个非常愚蠢的人,并且不明白赖利的评论应该是戏弄/伤害;他不会受到影响。或者假设他有一些完全古怪的东西(“是的,但火星上有峡谷”)。

相比之下,如果那里有第三个人(比如说 George 和 Reilly 都在追求的爱情对象),这个毫无意义的自恋零赌注游戏就变得相关了:爱情对象可以对彼此进行评估,并奖励胜者的地位。这并不总是两者中最聪明的。你也可以想象一个乔治说“对不起,我有饮食失调症,我认为你这样欺负我是令人难以置信的耻辱”的世界。然后第三个人决定是把这看作是 Reilly 开了一个搞笑的笑话,而 George 脸皮太薄,无法接受,还是 Reilly 说了一些冒犯的话,George 勇敢地叫他出来。至关重要的是,如果她愿意,她可以让她的决定取决于她是否更喜欢 Reilly 或 George,或者未来是否会成为更好的盟友——所以这部分是身份交易,部分是身份——测试。

但在实际的Seinfield情节中,没有爱情。乔治和赖利试图互相得分,完全没有意识到这是没有意义的。对于 Rao 来说,这是毫无头绪的一个明确标志——任何有社交能力的人都会意识到没有任何地位可以得到或失去,整个游戏毫无意义。

所以失败者的笑话是 3 人以上,而无知的笑话是 2 人。继续这个模式,一个反社会的笑话必须是给一个人的——小丑自娱自乐,完全不关心其他人是否欣赏它。

五。

反社会者不一定是邪恶的。他们只是。 . .对其他人不屑一顾。他们可能仍然遵守规则,因为这样做对他们有利,或者因为他们个人选择遵守一些他们碰巧喜欢的道德准则。但他们不渴望任何人的认可,甚至不渴望抽象的概念。

如果无知者来自于停滞的发展,而失败者来自于正常发展及其伴随的地位经济学,那么反社会者是由一种黑暗的启蒙形成的。他们有那么一刻意识到没有什么是真的,一切都是允许的。饶诗意的一面写道:

社会病态并不是要从社会现实的脸上撕下一个特定的面具。这是关于认识到没有社会现实。只有面具。对于那些倾向于相信人类状况有一些特殊之处的人来说,社会现实作为一种日益复杂和专业化的虚构的等级存在,这使我们的现实与宇宙的其他部分区分开来。

There is, to the Sociopath, only one reality governing everything from quarks to galaxies. Humans have no special place within it. Any idea predicated on the special status of the human — such as justice, fairness, equality, talent — is raw material for a theater of mediated realities that can be created via subtraction of conflicting evidence, polishing and masking.

Mask is an appropriate term for any social reality created through subtraction, because an appearance of human-like agency for non-human realities is what the inhabitants require. By humanizing the non-human universe, we make the human special.

All that is required is to control people who believe in fairness, is to remove any evidence suggesting that the world might fundamentally not be a fair place, and mask it appropriately with a justice principle such as an afterlife calculus, or a retirement fantasy.

[…]

When a layer of social reality is penetrated and turned into a means for manipulating the realities of others, it is automatically devalued. To create medals and ranking schemes for the benefit of the Clueless is to see them as mere baubles yourself. To turn status-seeking into a control mechanism is to devalue status.

To devalue something is to judge any meaning it carries as inconsequential. In terms of our metaphor of masks of gods, the moment you rip off a mask and wear it yourself, whatever that mask represents becomes worth much less. So the Sociopath’s journey is fundamentally a nihilistic one.

The climactic moment in this journey is the point where skill at manipulating social realities becomes unconscious.

Suddenly, it becomes apparent that all social realities are based on fictional meanings created by denying some aspect of natural, undivided reality. Reality that does not revolve around the needs of humans.

The mask-ripping process itself becomes revealed as an act within the last theater of social reality, the one within which at least manipulating social realities seems to be a meaningful process in some meta-sense. Game design with good and evil behaviors.

Losing this illusion is a total-perspective-vortex moment for the Sociopath: he comes face-to-face with the oldest and most fearsome god of all: the absent God. In that moment, the Sociopath viscerally experiences the vast inner emptiness that results from the sudden dissolution of all social realities. There’s just a pile of masks with no face beneath. Just quarks and stuff.

Both Losers and Clueless are trying to manipulate other people’s impressions of them. Sociopaths are trying to manipulate reality. Reality includes other people’s impressions – if your goal is to become President, in some sense you care what the electorate thinks of you. But it’s an instrumental goal. Sociopaths crave the Presidency (or whatever) and use other people’s good opinions as stepping-stones. Losers and Clueless crave the good opinions directly.

Once you stop craving other people’s good opinions, you lose some mental blocks that would normally prevent you from coming up with manipulative strategies. Rao says the most basic Sociopath manuever is “heads I win, tails you lose” – coming up with some way of arranging systems so that they get the credit for good results while avoiding the blame for bad ones. A simple strategy is to come up with a plan and appoint a Clueless pawn as Director Of The Plan. If the plan goes well, it was always your idea and you hand-picked and mentored the person who carried it out. If the plan goes poorly, it was always the director’s idea, you maybe thought it had some promise but he clearly bungled the execution. But this is a weak 101-level version of the maneuver;the real thing involves a bunch of bureaucracies, committees, and total deniability. Rao theorizes that most of the middle layers of companies are giant and powerful machines built by Sociopaths to guide and redirect the flow of blame and credit.

Is everyone else against this? Do they view it as duplicity and oppression? Rao says no. Sociopaths aren’t just CEOs. They’re priest-kings, creating meaning for everyone else.

The Clueless demand a world of legible rules, legible rewards and punishment, and a legible Authority tracking everyone’s balance. Sociopaths, who create companies, religions, governments, and every other form of authority, help Clueless people live in the legible gamified rank-able worlds their minds crave.

I’m less able to follow Rao’s explanation of “Loser spirituality” and how Sociopaths control it. My guess is something like: Losers “worship” positive emotions, belongingness, and “good vibes”, within carefully obfuscated conspiracies of mutual status-blindness. These aren’t really capable of dealing with the real world: a typical fiction is that “we’re all really talented and gave our all on this project”, but in fact the project might be failing. Sociopaths are outside those conspiracies and outside local status competitions, ie your CEO isn’t going to share banter over a glass of beer with you. So they are allowed to (carefully, emotionlessly) communicate/represent/convey reality to the status-maintenance conspiracies in a way where no particular member loses status by admitting reality first.

Although in some vague sense the Sociopaths are oppressing and manipulating everyone else, this isn’t how it feels from the inside: both Clueless and Losers are grateful to the Sociopaths for taking the burden of confronting reality off their shoulders. If the Sociopath fails at this, and a Clueless or Loser has to confront reality unmediated, they’ll either have a very bad time but eventually bounce back, or become a Sociopath themselves.

VI.

So that’s The Gervais Principle . Is any of it true?

I don’t find myself or the people I know best falling clearly into any of these archetypes. They’re useful to have around. I can see pieces of all of them. But none are a great match.

I can see bits of myself in the Clueless archetype. I like legible systems. I’m the person who did really well on standardized tests, really badly at networking, and ended up in medical school because it was the highest you could go on test scores alone. I’ve occasionally suggested that all politics should be replaced with some kind of system for calculating how much utility every option has, then doing whichever one is best (bonus points if it’s on the blockchain).

But I’m bad at listening to authority figures,and quit my last job to start my own company. Also, Clueless people are supposed to be bad at using language in original ways, and I’m a professional writer.

Sociopaths are supposed to fiercely distrust collectivism and come up with their own, usually utilitarian-inspired morality, which I identify with. But I can’t manipulate my way out of a paper bag. Also, a few weeks ago I got in an argument with a clerk over the right amount of change, after double-checking it turned out I was wrong and the clerk was right, and even though this was in an airport and I will definitely never see that clerk again, I felt embarrassed about the interaction for hours, and still feel pretty bad about it. Doesn’t really feel very ubermensch-ish or transcended-the-need-for-other-people’s-good-opinion-y.

I have a group of friends, and within that group of friends I’m acutely aware of the things I’m unusually good at vs. bad at, and I worry a lot about whether my strengths qualify me to be a member in good standing. My status within that group is illegible and I prefer that to the alternative. Does that make me a Loser ?

Who controls the microphone in my head? Whose approval do I crave? When I was younger, I remember pretty vividly that it would be whoever I had a crush on at the time. When I started blogging, it was very clearly my blog audience. But sometimes it gets hijacked by random store clerks. I particularly remember being invited to an event with some big name tech people, fretting about whether they would like me, exerting some willpower to remind myself that I was valid with or without their approval, and then realizing afterwards that what I had actually done was fantasize about how if I wasn’t obviously craving their approval, they would be impressed by my independence and put-togetherness and respect me even more.

So fine, I (and the few other people I know well enough to use as examples) don’t naturally fall into any of these categories. Whatever, Rao said (in one sentence) that everyone has multiple types. But then what’s the use of this categorization system? If I invent three random types of people:

-

Green: introverted, long hair, likes the cold, complains too much

-

Red: cheerful, gets mad at little things, loves pets and children

-

Blue: financially savvy, bad at romance, natural leader, enjoys biking

…then most people will find that they have some traits of each, but that’s just a natural result of the system being made up and useless.

Maybe the problem is I’m using this as a psychological type system, but it’s actually supposed to be a business book after all? The namesake principle claims that overperforming Clueless get promoted to middle management, and underperforming Sociopaths get promoted to the top. This ought to be testable. Suppose we looked at a sales firm, or an investment bank, and correlated first-year sales/profits with promotions. I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that overperformers get promoted to the next level up – after all, the naive ordinary model says you get promoted for good work. Surely most people who underperform their first year won’t get promoted, but the Gervais partisan could say that yes, only a few very special underperformers are real Sociopaths. So maybe a better example would be to look at the top levels of corporations where performance is easily measured, and see how many of the big executives overperformed / underperformed / normalperformed during their first year. I would naively predict the top echelons would be made of former normal-to-over-performers, so if someone found they were in fact underperformers that would be a big update for me in favor of all of this Gervais stuff. I can’t find a dataset that would tell me this, but if any of you are very high up in big corporations, please poll your peers and let me know what they say.

Also, I don’t get the impression that most top executives are people who had traumas that caused them to see the unmediated Real and achieve dark enlightenment. Most of them seem to be the kids of other rich people, who did well at school and have some moderate amount of business talent. I’m guessing the average single mother trying to make ends meet as a receptionist has had ten times more unmediated-Real-experiencing than they ever will. I don’t know, maybe I’m using an unsophisticated definition of trauma and the Real here.

Finally, it just seems totally wrong to me that the highest-status and lowest-status members of groups/clubs/societies are legible, and everyone in the middle isn’t. I am thinking of some non-formal groups I belong to, and the highest- and lowest- status people are often as confusing as everyone else. The exceptions are formal organizations with presidents or whatever, but even there I couldn’t tell you who the lowest-status person is.

VII.

That last section might feel harsh, so I want to stress that I liked a lot of things about Gervais Principle .

Gervais Principle feels like what psychoanalysis would be like if it weren’t so devoted to making itself incomprehensible. It explained its theories clearly and gave good examples of each. Even though it stuck to really traditional psychoanalytic ideas (the theory of people getting stuck at developmental stages is classic Freud – see eg anal-retentivity , oral fixation , etc) it vastly exceeded the source material in clarity, plausibility, and ability to avoid naming all of its concepts after barely-related bodily orifices.

In particular, I feel like I better understand some of the ideas from Sadly, Porn . People’s desire to subject themselves to an order created by sociopaths. Everyone keeping a ledger of status transactions. Terror of acting openly, and how it breeds bureaucracy and excessive layers of management. It’s all in here.

Lacan claimed there were three different personality structures: neurotic, psychotic, and pervert. Suggestive, but I can’t squeeze these into matching Rao’s triad. For example, Lacan’s neurotics are defined by being subject to Law, and potentially by wanting to become the object of others’ desires, which sounds Clueless. But Lacan says neurosis is the most developed stage, whereas Rao says Clueless is the least . Likewise, Lacan says psychotics are incapable of using language normally, instead retreating to stock phrases – a suspiciously good match for Rao’s Clueless description. But Lacanian psychotics are most able to act and least dependent on other people’s approval, which is totally the opposite of Rao’s system.

Clinical Introduction hints at a rare personality type who has passed beyond neurosis, and is able to have normal healthy self-motivated desires that are not just the desires of others. It doesn’t dwell on this type, because they rarely see psychoanalysts, but it sounds like a good match for Rao’s Sociopaths. That would mean we have to map all three main Lacanian types into Rao’s Clueless and Losers – but I have no idea how to do this faithfully.

So I am less impressed by the typology itself than in the book’s ability to ask questions – or, more precisely, to make the reader ask questions. This is its “organizational literacy” – when confronting people or groups, you can ask things like:

-

What narrative script is a person relying on in order to maintain their sense of specialness?

-

Which idea/ghost/model controls the microphone that produces the voice in some person’s brain at any given time?

-

How has the bureaucracy of this organization been designed to redirect credit and blame in ways that serve its leaders?

-

What sources of reward is this person addicted to, and how has that changed the lens through which they see the world?

Most people have a special place in their heart for the book that first made them understand the idea of status economics. Gervais Principle does a good enough job with this that I’m sure it had a profound effect on some people. For me, that role was already taken by an unusually good college psych textbook, plus Robin Hanson’s blogging as remedial lessons, so I feel less transformed.

Still, it never hurts to get reminders. This book made me more aware of approval-seeking and status in my life for a little while. I might try Be Slightly Evil next and see if it enlightens me further. You read Nietzsche in freshman philosophy, and for a few weeks you vaguely feel like you ought to be the ubermensch. But that’s hard, and it’s not really clear why it would even be a good thing, so eventually you forget about it. The Gervais Principle has a similar effect.

By the way, Gervais Principle was originally written as a sequence of six free blog posts. It’s good enough and short enough that, if you enjoyed this review, you might as well read the whole thing. You can find it here .

原文: https://astralcodexten.substack.com/p/book-review-the-gervais-principle